For the first time in our history, America’s annual interest payments to service our debt are set to exceed defense spending. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the federal government will spend $870 billion on interest payments this year compared to $850 billion on defense. Whether you think the risks of climate change are zero, near zero, somewhat serious, or the existential threat of our time, as President Biden insists, this milestone raises serious questions about our nation’s ability to give sustained attention to an issue like climate change.

Our debt should be considered a climate problem for three reasons.

First, debt can slow innovation, which is important because innovation is by far the best way to address climate change. History shows (as this “hockey stick” graph illustrates) that nothing has done more to lift people out of poverty and solve vexing problems than innovation.

For most of human history, more than 90 percent of all people on earth lived in extreme poverty. In 1900, that was true for 75 percent of the world. As late as 1960, more than half of all people lived in extreme poverty. Today, that’s the case for less than 10 percent of the world.

>>>READ: Surprise! Pork Barrel Politics is Back

Economic growth in England tells a fascinating story. In the year 1270 (when William Wallace was born), the per capita GDP in England was £806. It took more than 400 years for per capita GDP to double when the figure hit £1,614 in 1690. In the 1800’s, that figure doubled again from £2,332 in 1800 to £4,871 in 1900. After 1900, growth exploded and the upward “hockey stick” emerged. By 2016, England’s per capita GDP was £28,693 – a fivefold increase from 1900.

What caused this explosion of growth? It certainly wasn’t started by any top-down, government-led effort. There was no entity to wage a Global War on Poverty. Instead, it was triggered by factors like rising literacy rates, the transition from burning trees to fossil fuels, the Industrial Revolution, and advances in sanitation and health care. Stable governments, free societies and much-maligned alliances like NATO then helped keep innovation on its upward trajectory.

As I discussed with Rep. Estes recently, interest payments are real money that is diverted from more productive activities to less productive ones. The innovations necessary to move the world to lower emissions technology will take longer to be discovered and deployed when interest payments are taking money out of the hands of creative people.

Second, debt diverts scarce resources from not just the private sector but the public sector.

To be clear, the most important thing the government can do to promote innovation is to get out of the way. Every dollar not spent in Washington, D.C. is a dream realized by an entrepreneur somewhere in America. Biden’s “whole of government” approach to climate change is myopic and foolishly puts government at the center of our national life to the exclusion of people doing the actual work of innovation. Top-down industrial policy is unimaginative and doesn’t work over the long haul. As we’ve shown, free economies are twice as clean as less free economies because free economies enable “whole of society” bottom-up entrepreneurship and empower private property owners to develop natural solutions.

>>>READ: For More Innovation, Unleash More Economic Freedom

Demagogic partisan Democrats describe this philosophy as anti-government but being appropriately skeptical of government and realistic about its limitations is the key to developing durable policies. Government can have a very limited role in research and development, particularly regarding national security (i.e. fusion), but should avoid playing venture capitalist. The best way to make something expensive is for the government to make it “affordable.” When the government adopts a subsidy-heavy approach it tends to punish winners and prop up losers. The wisest posture for government is to be tech-neutral.

What the federal government can do under our Constitution (Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3) is regulate interstate commerce and make appropriate tech-neutral investments in infrastructure.

Even though the U.S. has invested significant funds into infrastructure through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), The Economist notes that in real terms U.S. spending on infrastructure has fallen. This gap is exacerbated by the fact that regulatory inefficiencies are preventing taxpayer dollars from stretching further.

If Congress was interested in setting priorities, much of that funding could be found by smartly downsizing our bloated administrative state. Yet, the daunting task of forcing Congress to reprogram funds is made even more difficult by massive looming shortfalls in our safety net programs. Over the next 75 years, Medicare and Social Security will make up 95 percent of our $79.5 trillion in unfunded liabilities. Medicare faces a $52.5 trillion shortfall while Social Security is $23.3 trillion in the red. Good luck persuading any rank-and-file member of Congress to adequately fund infrastructure by taking money away from Social Security and Medicare.

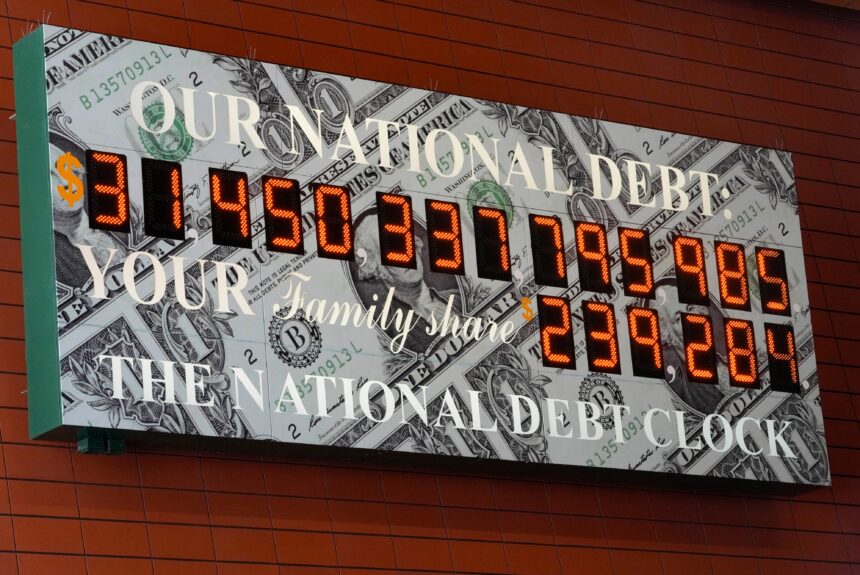

Finally, Admiral Mike Mullen, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff under President Obama is still right that “The most significant threat to our national security is our debt.” Mullen made that comment in what seems like another era, but it was only 14 years ago when our debt was at $13.5 trillion (today it’s at $34.2 trillion).

Economists disagree about the threat of unsustainable debt loads but common sense, the Law of Finite Resources, and economic history suggest that nations who insist “This Time is Different” come to regret their complacency. The greatest threat to climate progress isn’t climate denial but deficit denial and a refusal to recognize how unsustainable spending threatens innovation, infrastructure, and our national security.

The views and opinions expressed are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of C3.