Amid the fog and pleasant chill, children in the Phlangwanbroi village, 150 km (93 mi.) from Shillong, take an oath to protect the precious forest, biodiversity, and western hoolock gibbon. Loud and musical sounds of endangered gibbons from hills surrounding the village in this Himalayan state of Meghalaya in North East India, can be heard in the background, as local youth turned tourist guides take kids and tourists for a jungle walk in the hills bordering Bangladesh.

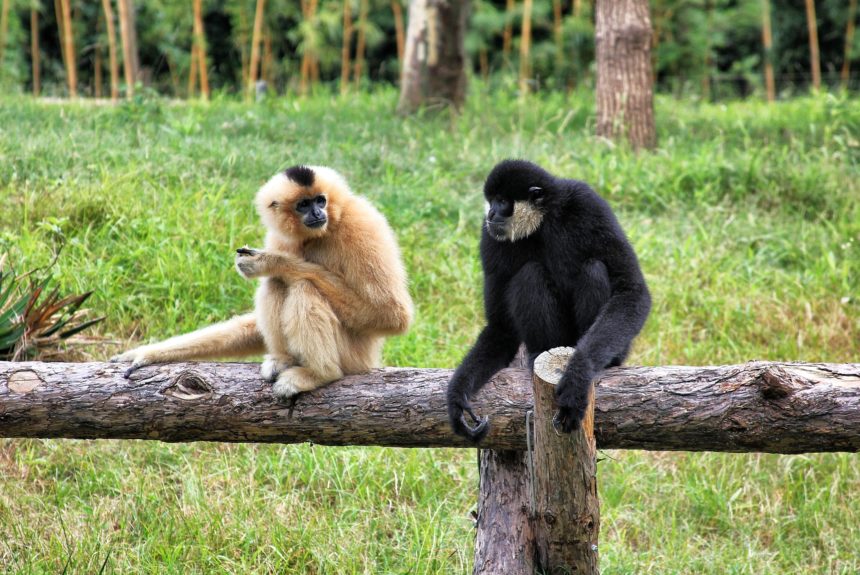

Gibbons, small unique apes, are listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Gibbons are Schedule One protected category under India’s Wildlife Protection Act, of 1972.

>>>READ: How to Fix the Endangered Species Act

There are 35 to 40 gibbons, locally called “hooleng jingrwai” by the Khasi, a local tribe, that are found in five villages in the region, including Phlangwanbroi. These five villages make up Hima Malai Sohmat, one of the kingdoms of the Khasi tribe.

90% of endangered gibbons’ estimated population is lost due to habitat destruction, habitat fragmentation, habitat degradation, hunting, and neglect by the government, according to one expert. It is estimated that around 3,000 western hoolock gibbons are remaining in India.

“Tribal, guests, and tourists would hunt gibbons till 2017-2018 regularly. That is when we decided to ban hunting in Hima Malai Sohmat. To avail alternate livelihood options, we trained local unemployed youth as tourist guides, cooks, and administration work. We have made a local cooperative society to groom local youth to get into hospitality,” says Tyngshain Dewkhaid, a 45 year old local school teacher.

B Dewsaw, King of Hima Malai Sohmat, set a fine of Rs 5000 ($67) for hunting gibbons in 2018. The Khasi tribe decided to not touch half the forest, 40 km (24 mi.) to conserve the habitat of gibbons.

“Tribal practice [is] shifting cultivation [which] means [that] every year they cultivate on a new patch of forest as per their tradition. Thus they are leaving half of the forest land on which they could cultivate to save [the] habitat [of] gibbons. This is a very generous decision on the part of [the] tribe who are not economically well off,” reports Dewsaw.

Residents founded Malai Sohmat Tourism and Multipurpose Cooperative Society in 2006 and began operations in 2015. Over 1000 tourists have visited and enjoyed spotting gibbons, trekking, kayaking, camping, and swimming. Tourists also spot deer, wild boars, and other mammals that are in these forests.

The society, with assistance from Conservation Initiatives, has hosted the Annual Gibbon Conservation Festival in November or December every year since 2018. The festival aims to create awareness about the importance of the conservation of nature through awareness talks and jungle walks for locals and visitors. They also screen documentaries about gibbons and how to protect biodiversity at schools, colleges and communities in nearby villages.

>>>READ: The Mangrove Foundation is Bringing Sustainability to India

“I am a school dropout and was not interested in agriculture like my parents do. I was thinking of migrating to Guwahati to work as a labourer at a construction site that would have [paid] me a good amount of money. But I got to know about this opportunity and became a guide. We were [taught] how to talk to tourists, basic English, how to protect [endangered gibbons] and so on.”

“Besides, we also explain the history and culture of the Khasi tribe and take tourists to see gibbons in the early morning. I earn Rs 500 ($7.50) per tourist. I have been a guide to over 100 tourists though the number of tourists has been low since the pandemic began,” tells Alphaius Lawphniaw, a 20 year old guide.

“We don’t want a crowd of tourists as we don’t want to stress local resources. We want to develop the place in line with tourism for conservation and for biodiversity. Now we started to get tourists again after a gap of two years when traveling was banned due to the Corona-induced pandemic,” tells Dewkhaid.

“Most importantly, there have been no incidents of hunting gibbons since 2018-19 when locals decided to ban hunting and protect their habitat. And this is a welcome change,” tells Sachin Gavade, Divisional Forest Officer, Meghalaya.

Dewsaw proudly says that local tribes can hear the music of gibbons once again and are confident that their numbers must be rising.

Varsha Torgalkar is an India-based independent journalist. She covers public health, climate change, rural economy and travel. She has written for LA Times, SCMP, Asia Democracy Chronicles, Huffington Post and many Indian news websites. She has been a fellow of Earth Journalism Network, UNICEF and National Foundation of India. She has been a recipient of the PII-ICRC award for the best story.

The views and opinions expressed are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of C3.