In recent months and weeks, Congress has shown keen interest in advancing nuclear power. With strong bipartisan support, both chambers passed bills to make it easier to build nuclear power plants in the U.S. Neither has made it to the president’s desk, signaling that there’s much more work to do. One priority is to strengthen the nuclear fuel supply chain.

Over 99% of naturally occurring uranium consists of the isotope U-238, which is not fissile and cannot sustain a reaction in a thermal-neutron reactor. As a result, the U.S. relies on U-235, which only makes up .7% of natural uranium, to power its fleet of nuclear reactors. Increasing the share of U-235 to convert natural uranium into workable fuel, which is called low-enriched uranium (LEU), requires a process called enrichment. Done through gaseous diffusion or gas centrifuges, enrichment uses the mass difference of U-238 and U-235 to separate the two isotopes and increase the concentration of U-235 from .7% to as much as 5%, creating LEU.

>>>READ: Congress Charts a Path to Unleash American Nuclear Power

America’s supply of natural uranium and LEU is highly dependent on other nations. In 2022 imported natural uranium came from Canada (27%), Kazakhstan (25%), Russia (12%), and Uzbekistan (11%). The remaining 16% was sourced from a combination of the U.S., Germany, South Africa, and others.

At one point the U.S. had ample enrichment supply with facilities in Kentucky and Ohio. Today, it only has one domestic facility in New Mexico. Operated by Urenco, it is capable of meeting only one-third of America’s enrichment needs. As a result, the U.S. relies heavily on Russia, which owns 47% of the global enrichment supply. In 2022, America was the largest importer of Russian–enriched uranium, accounting for 42% of Russia’s exports.

America’s overreliance on enrichment not only presents a challenge to the current supply chain but to future ones as well. A majority of the designs of advanced reactors rely on high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU), which is LEU that is enriched to levels between 7% and 20%. While the U.S. is already dependent on Russia for its supply of LEU, it is even more reliant on it for HALEU as Russia is the only commercial supplier of this fuel in the world. The challenges of this reliance have already been realized with NuScale’s small modular reactor pilot project in Idaho, which NuScale canceled due to inflation, unclear regulations, and a lack of readily available HALEU.

Reducing U.S. dependence on adversarial nations for such a critical part of the nuclear energy supply chain is important for energy security, national security, and innovation. Encouragingly, the private sector and policymakers are providing solutions.

Last year Congress passed the Nuclear Fuel Security Act, a bipartisan, bicameral bill that aims to bolster the domestic supply of LEU and HALEU. The bill created the Nuclear Fuel Security program which would require the Secretary of Energy to enter into two or more contracts with domestic suppliers, or suppliers from allied nations, to acquire not less than 100 metric tons of LEU per year by 2026. For reference, the U.S. purchased 18,370 metric tons of uranium in 2022. The program would also direct the Department of Energy to purchase 20 tons of HALEU per year from domestic nuclear power companies.

In addition to the Nuclear Fuel Security Act, the federal government has also set aside $700 million to support the domestic supply of HALEU through the HALEU Availability Program in the Inflation Reduction Act.

The goals of the Nuclear Fuel Security Act would be better supported by a more efficient permitting process. The prescriptive and onerous regulations that the nuclear industry has had to endure have made increased costs and made new nuclear power less economical. A risk-averse culture at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission has discouraged an efficient build-out of nuclear power, which has subsequently stifled investment in American enrichment and made the domestic industry unable to compete with cheap Russian uranium. Streamlining regulations for nuclear power and uranium mining, as well as easing the cost of doing business, would signal to enrichers that nuclear power is here to stay in the U.S.

>>>READ: Three Federal Innovation Programs That Lawmakers Should Prioritize

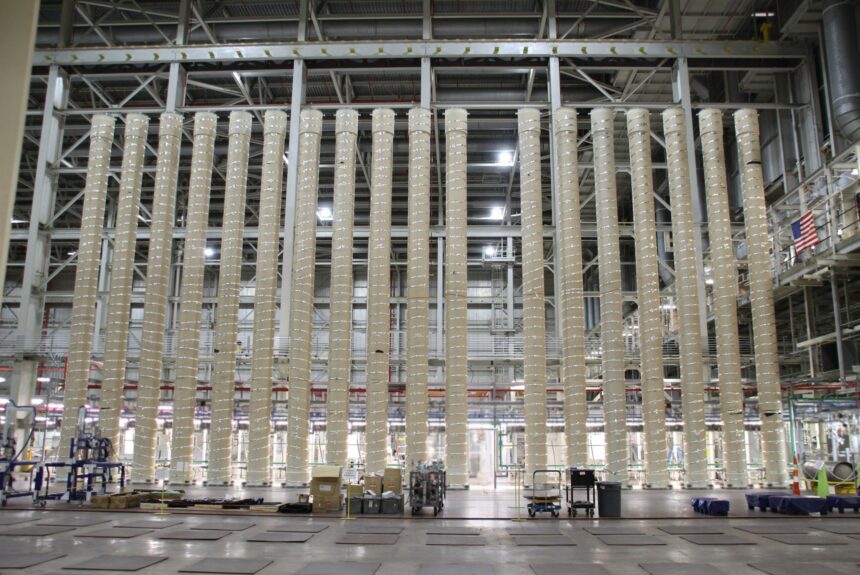

The federal government has also made investments in the nuclear fuel supply chain through the Advanced Nuclear Fuel Availability Program and the Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program (ARDP). Under the Advanced Nuclear Fuel Availability Program, DOE has entered into an agreement with Centrus Energy to produce the country’s first supply of domestic HALEU. The partnership has already yielded an initial 20 kilograms of HALEU and Centrus plans to boost annual production to 900 kilograms by the end of this year. An impressive feat, this level of production is well short of the 40 metric tons that the DOE says is needed by 2030 to build out a supply of advanced reactors.

Centrus has also entered into an MOU with advanced reactor company OKLO. Under this agreement, OKLO will power Centrus’ enrichment facility and Centrus will sell its HALEU to OKLO.

The ARDP, meanwhile, is engaged in a public-private cost share to fund two demonstration projects, one of which is TerraPower’s Natrium reactor. This 345-megawatt sodium-cooled fast reactor has the capacity to run on spent fuel, which America has in ample supply. While the U.S. does not currently recycle spent nuclear fuel, in large part because it is more economical to buy new, up to 96% of spent fuel can be reused. TerraPower is currently working to deploy its Natrium reactor at the site of a retiring coal plant in Wyoming. If successful and financially viable, a fleet of fast reactors could help to solidify the fuel supply chain.

Congress has signaled support for traditional and advanced nuclear power. However, before the U.S. can build out a fleet of reliable, carbon-free energy, it must first secure its supply of nuclear fuel. Expediting domestic production, reducing regulations, partnering with allies, and investing in innovation will reduce supply chain disruptions and accelerate a build out of nuclear energy in the U.S.

The views and opinions expressed are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of C3.